The ocean is famous for its endlessness and its calm. And yet sometimes everything happens at once. Thousands of dolphins appear around the ship and race past the bow back down. “I want one for a pet!” calls a boy on deck. In the background, a freighter moves lazily through the channel in front of the Californian coastal city of Santa Barbara.

And then, very close to the boat, a humpback whale heaves itself out of the water, seems to hover in the air for a moment, and then splashes on its back. The animal is as long as a bus, and it actually has no natural enemies. Only the freighter threatens his life. He could run over him. Because it has become narrow in the seemingly endless ocean.

This all sounds like an unlikely problem. 71 percent of our earth is covered by the ocean. On average, they are over 3,700 meters deep. If you turned the ocean floor inside out, you would create a world far larger than ours on land. The Pacific is the largest and, at up to 11,000 meters, also the deepest ocean. It is shared by whales and dolphins, corals, fish and fishermen, research vessels, submarines, and freighters carrying goods from one continent to another. In 2021, around 90 percent of world trade was carried out by sea.

The ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, just south of Santa Barbara, and San Francisco, just north of it, are among the busiest cargo ports in the world. Nowhere off the coast of the USA do so many ships cross as here. Right where some of the most important migratory routes of blue, gray, humpback and fin whales are. “Every year animals die here because they are rammed by cargo ships,” says Callie Steffen. She is part of one of the research teams on the west coast of the USA who want to prevent this in the future.

An app to save whales

“Be careful not to get seasick,” recommends Captain Dave Beezer to the passengers of the Condor Express straight through the loudspeaker. He also points out the onboard canteen’s breakfast and lunch menus and that seven California sea lions are sunning themselves on a buoy to the right of the boat. Callie Steffen is leaning against the railing of the whale watching boat. Captain Beezer takes her out that day in late November; the two have known each other since Steffen moved to Santa Barbara in 2018. The 32-year-old wears sunglasses and a ponytail. Her peaked cap and Patagonia fleece jacket have the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory logo printed on them: a wave that becomes a line graph. Pretty fitting for Steffen’s job on the Whale Safe project. She evaluates how whales and ships move, when they could meet – and above all, how they pass each other.

To map whales and their routes, marine biologists, oceanographers, programmers and marine acoustics experts have developed a website and app for the Santa Barbara coast. Anyone interested, but especially shipping companies and captains, can use it to see in real time whether there is a whale nearby.

The app has also been available for the coastal region off San Francisco since September. There, the Marine Mammal Center, the world’s largest hospital for marine mammals, is responsible for whale safety. To reach it, head towards Sausalitos over the Golden Gate Bridge, which separates the vast San Francisco Bay from the rest of the Pacific.

“We get 10,000 to 15,000 calls a year from people reporting a sea animal in distress. We treat about 800 animals a year here, mainly seals, otters, sea lions – and their babies. Dolphins are also less common,” says Kathi George.

The engineering graduate used to work in the tech industry, lost her job when the dot-com bubble burst in 2000 and then started something completely new as a volunteer at the Marine Mammal Center. Today, she leads the center’s whale and dolphin conservation research department and field operations.

“My first assignment was with a sea lion whose windpipe was cut by a tangled fishing line. It was bubbling out of its throat in a strange way. At that moment, I thought about my studies, where I had learned how to make products more durable and cheaper. With this one mentality we are destroying the planet today.”

A freighter broke Fran’s neck

“We estimate that about 80 blue, fin and humpback whales die each year from collisions off the US West Coast,” says George. “And that’s just the endangered species, last year we also found 15 dead gray whales.”

A research group used whale and ship routes for the US West Coast to model how many whales die there each year (Plos One: Rockwood et al.: 2017, Frontiers in Marine Science: Rockwood et al., 2021).

Kathi George, Callie Steffen and their teams are far from finding all dead whales. In 2018 there were 13 blue, fin and humpback whales, in 2019 one more. In the pandemic year 2020 there were only three, a year later eleven again. Six have been found so far this year. Most recently, it was Fran, a particularly often-photographed humpback forest lady, who washed up dead on the shore near San Francisco at the end of August. The Marine Mammal Center autopsy revealed that a freighter broke the neck of the 17-year-old whale in the collision.

Researchers like George and Steffen assume that only about ten percent of the whales killed in this way are found. After all, if a 300 meter long freighter rams a maximum 30 meter long whale, the captain probably doesn’t even notice. In May 2021, a ship arrived in San Diego with two dead fin whales hanging from it. The crew only noticed this when the mother and her calf floated to the surface of the water in the harbor. In November 2021, a high-speed ferry dismembered a sperm whale off the Canary Island of La Gomera without realizing it.

The Whale Safe research project aims to prevent incidents like these. The real-time data shows where whales are and where freighters should therefore slow down. Since the start of the project in 2019, a buoy with an acoustic sensor has been listening in the Santa Barbara Channel to see whether whales are singing nearby; an algorithm checks which species it is. The researchers also use satellite data to check where favorable water conditions could attract the particularly endangered blue whales. Above all, however, it is crucial that people report what they see: Whenever someone – a captain, a family whale watching, a jogger on the bank – sees a whale, he or she can enter a whale alert in the app.

A whale is always drawn to where it can find food

There is also a whale alarm on the Condor Express, the whale watching boat. The captain slows down, he sees what many passengers have not yet discovered: “Two whales on the right side”. Everyone runs to the starboard side of the boat. It splashes up several hundred meters away, one of the whales has exhaled. “Wow!”, “There they are!” shouts from all sides. “I’m guessing humpback whales,” says Steffen. “Can we get closer?” a girl asks her parents.

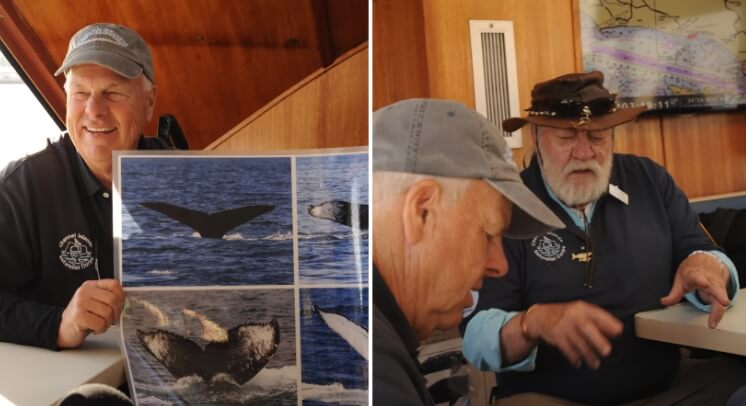

The Condor Express whale-watching boat brings tourists and whales together in the Santa Barbara Islands Marine Protected Area. Boats are allowed to approach whales up to a maximum of 100 meters. “But the whales are often curious themselves and come to us,” says Steffen. There are adults and children on deck, many of whom only know whales from books, films or amusement parks. There are also three so-called naturalists on board, nature connoisseurs who want to do something useful with their time now that they are retired.

“I used to work in the oil industry and now I want to do something for nature,” says one of them.

“I’m the rookie of the three of us,” says Del Hanson. “I’ve been going out there for seven years, Ken for 17 years.”

They carry small models of the whales and posters to tell passengers which whale is hiding beneath the surface of the water.

At the end of November, blue whales, fin whales and humpback whales are the most common in this area. They are all here to feed before heading south, up the coast, along the Mexican state of Baja California or further into Costa Rica. The marine reserves off Santa Barbara and San Francisco are among the most fertile feeding grounds in the world. Each whale species, even each own population, follows different routes and has different feeding habits. But they are always drawn to wherever their favorite food is. The gray whales, for example, only pass off the coast of Santa Barbara around January, Steffen explains, because they were still in the Arctic to enjoy their favorite dish – copepods.

Fin whales, humpback whales and blue whales feed primarily on krill, tiny crustaceans that flock off the coast of California at this time of year. With a single “gulp” the blue whale, the largest of them, takes in up to 80,000 liters of water and millions of small crustaceans. It is the largest among the big ones and can reach the length of an ICE car. He is the heaviest animal that has ever lived on earth. He still seems to need a protector.

Humpback whales are particularly curious

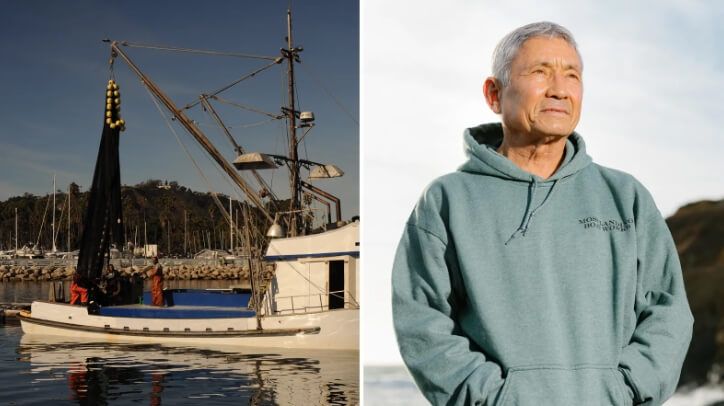

Off the coast of San Francisco, not only the freighters are a problem, but also the fishing, says ex-engineer Kathi George. “Whales have a lot of problems.” She has therefore been working with local fishermen for years to prevent the mammals from becoming entangled in the nets.

“Humpback whales are particularly curious. Sometimes they’ll nudge the nets with their noses to see what’s going on. Or if the line is a bit loose, they’ll play with it and roll in the water and get caught,” says George. “And they have no hands to free themselves again.”

2015 was a particularly disastrous year, she says: Because domoic acid, a naturally occurring marine toxin, had formed in the water, the fishing season for California crabs was pushed back. When it went off, however, many humpback whales also foraged near the coast of all places, as krill levels were lower than usual due to a heat wave in the ocean.

“In that month, 22 humpback whales were caught in fishing nets.”

A typical emergency for the Marine Mammal Center rescue team. If it is called, the helpers try to free the whale from the net from a small inflatable boat.

“We approach the whale from behind and place ourselves on its tail fin with a long pole that has a knife attached to it,” says George. “Usually we can only make a single cut, so we have to think carefully about where, so that the net doesn’t wrap itself around the whale again or even tighter afterwards.”

The crush disease

Three fountains are now splashing into the air in front of the Condor Express, and three backs of whales appear. Then, very briefly, three caudal fins. They are humpback whales, as Callie Steffen predicted. They can be recognized by the white spots left by barnacles on their fins or back, and by their powerful pectoral fins, which can be up to five meters long.

Most observers have their smartphones in their hands and want to take pictures. The nature connoisseurs pass binoculars back and forth. Some just stand there and marvel.

“When children see a whale for the first time, it’s magical,” whispers Steffen.

She herself was three years old when she saw the film that brought her here: Free Willy. It is about the friendship of a boy and an orca whale. He just doesn’t want to do the tricks he’s supposed to do in captivity, so the amusement park operator wants to kill him and cheat the insurance company. In the end, Willy the orca is freed in a spectacular rescue operation. The film has a happy ending. In reality, the whale that plays Willy was called Keiko and was also released into the wild after the big success of the film, but died of pneumonia in the wild a year and a half later.

“As a child I wanted to be a whale trainer, but today I find captive whales terrifying,” says Steffen. “We humans have this tendency to hug animals and want to get really close, I call it squeeze disease.”

The crush disease.

The relationship between humans and whales has always been ambivalent. Man has caged the animal for his own amusement, hunted to the brink of extinction. Now he runs him over with freighters and doesn’t even realize it. At the same time, the whale is emblazoned on baseball caps and T-shirts, people dedicate books and films to it and pay money to take a boat out for hours to get a lucky glimpse of its tail fin.

In the USA, the Endangered Species Act has been intended to protect blue, fin and humpback whales since the 1970s. It was only because of this law that Steffen and the Whale Safe team were able to get a reduced speed zone introduced:

“Off the coast of Santa Barbara and San Francisco, freighters of a certain size are required to brake to ten knots, so at 18 kilometers per hour.”

However, it is still voluntary whether the shipping companies adhere to it. According to Whale Safe’s annual report, ships slow down about 60 percent of the time when entering the safe zones.

The whales don’t realize that a ship is coming their way

It’s very quiet on board now. Then the three whales that showed up in front of the ship’s bow appear again. This time they are very close. They turn their heads towards the boat and let the waves rock them up and down. “This behavior is called logging,” says the captain through the microphone. The whales float on the water surface like tree trunks and rest”. Steffen adds:

“Humans breathe unconsciously, but whales have to think about every breath they take. Even when they are sleeping or resting, they can therefore only switch off one hemisphere of their brain.”

She takes her smartphone out of her fleece jacket again and wants to take pictures of the whales’ tail fins to enter them in the app.

“Each individual whale can be identified by the pattern on its tail fin. In this way, we can sometimes even follow the journey of individual whales virtually.”

You can always see the tail fin when a whale prepares to dive. In the case of the humpback whale, it is up to 200 meters deep and often between five and eight minutes long. But then he has to return to the surface of the water and take his next breath.

The small whale watching boat does not make the animals nervous, but rather curious. The problem is that even large freighters don’t make them nervous.

“Whales didn’t evolve in a busy ocean. They didn’t have to learn to perceive ships as a threat and swim out of their way,” says Steffen. “And they can’t pass the knowledge on either, because they’ll probably die if a freighter runs them over.”

Suddenly one of the humpback whales jumps out of the water, right in front of Steffen, with the freighter in the background. At that moment, even the researcher forgets that she actually wanted to take a picture.