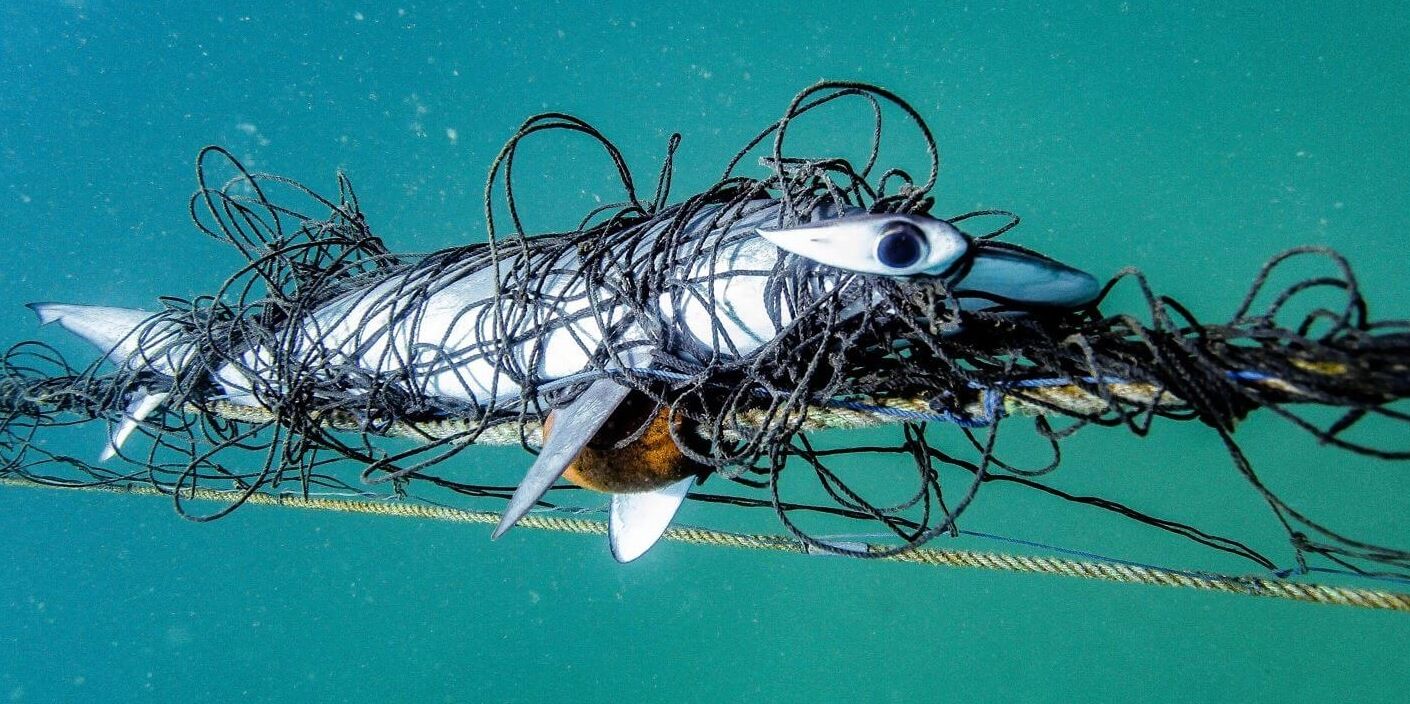

Over the past month, a heart-wrenching incident occurred as a baby dolphin and three young whales became entangled in shark control equipment off Queensland’s coast. The dolphin suffered critical injuries due to a drumline hook through its side, while two whales were eventually released, and one tragically drowned. Witnessing such cruel by-catch events, coupled with recent political encounters, has led me to believe that there exists a profound misunderstanding about the government’s shark control policies along Australia’s east coast. While the media has focused on Western Australia’s drumlines, the situation on the east coast, where Surfer’s Paradise alone boasts more drumlines than the entire Western Australia, has been neglected. As a native of New South Wales (NSW), a state that has culled sharks since the 1930s and still kills thousands of animals annually with beach nets, I feel compelled to shed light on the adverse economic and environmental consequences of this policy.

How do the shark nets work?

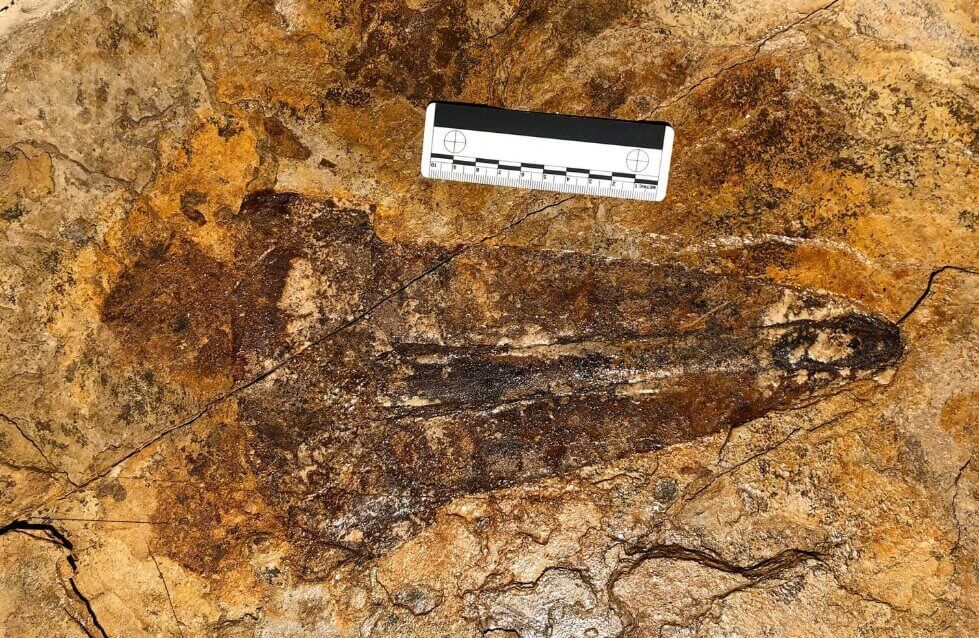

First and foremost, it is essential to understand that shark nets are not barricades. Their purpose is not to prevent sharks from approaching the beach. Instead, they are set up to entangle and kill animals passing by. These nets, approximately 150 meters wide and 6 meters tall, are usually placed at about 10 meters of water depth, allowing sharks to swim freely over and around them. In NSW, these nets are typically deployed for only eight months each year, and during each month, they are in place for merely 14 days, leaving extensive periods without protection.

Watch this short video for more information.

Are they protecting people?

The unfortunate truth is that shark nets do not significantly enhance beach safety. No scientific evidence proves that these nets make our oceans safer for beach-goers. A government report from 2009 stated that ‘the annual rate of shark attacks remained the same both before and after meshing commenced.’ While the number of shark fatalities has seen a decline since the nets were put in place, this is attributed to improved medical assistance, not the effectiveness of the nets.

Are they harming wildlife and ecosystems?

Regrettably, yes. The impact of shark nets on marine life has been devastating, resulting in over 15,000 animal deaths in NSW. Among the victims are approximately 100 species, including endangered turtles, dolphins, dugongs, rays, seabirds, harmless sharks, and rays. Shockingly, shark nets have also claimed the lives of orcas, little penguins, and even two people. Just last year, near my home, a baby humpback drowned in the nets while its mother watched helplessly. These deaths are not a trade-off for human protection but rather unnecessary casualties within an outdated system that fails to safeguard anyone.

How much does it cost?

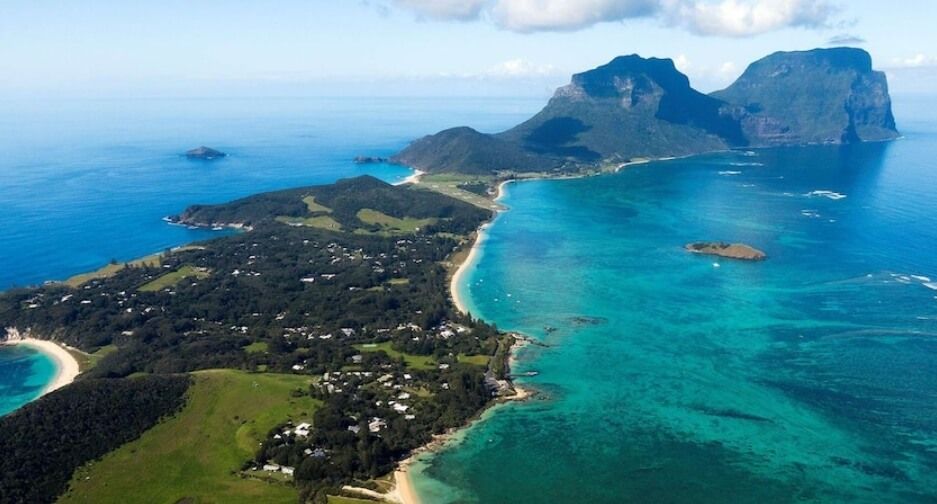

The NSW Shark Meshing Program incurs an estimated cost of about $1.4 million per year. This program operates on a contract of merely eight months and 14 days of each month, covering beaches between Wollongong and Newcastle.

Is there an alternative?

Fortunately, recent technological advancements, based on an improved understanding of shark behavior, have presented us with superior alternatives. The eco shark barrier offers an actual barrier without entanglement risks, while the clever buoy can detect shark size and movement patterns in real-time. We have come a long way since the 1930s and have viable alternatives that provide effective beach safety measures.

But am I going to get eaten by a shark?

Statistically, it is incredibly unlikely to be attacked by a shark – it is even less probable than being killed by a vending machine, struck by lightning, or hit by a falling coconut. However, every time we enter the ocean, we take a calculated risk, just as in any other aspect of life. In the rare instance of a shark bite, you will probably end up with an impressive scar (contrary to Hollywood’s portrayal). At the end of the day, let us embrace the ocean as the sharks’ natural habitat. When we enter the water, we are stepping into the territory of sharks and all other ocean creatures. That is what makes the ocean so incredible!

Can I do anything to help get rid of the nets & drumlines?

Yes! You can make a difference by joining local social media groups like #noNSWsharkcull, #noQLDsharkcull, and #noWAsharkcull, or participating in nation-wide initiatives like Sea Shepherd’s newly launched anti-shark culling campaign, Operation Apex Harmony. These campaigns aim to replace the nets and drumlines with alternatives that genuinely protect people without harming other animals. Together, we can advocate for beach safety measures that respect marine life and maintain the ocean’s natural balance. By embracing innovative solutions and coexistence with marine creatures, we can ensure a secure and sustainable future for our oceans.